Aimé Guerlain: Father of Modern Perfumery & Creator of Jicky

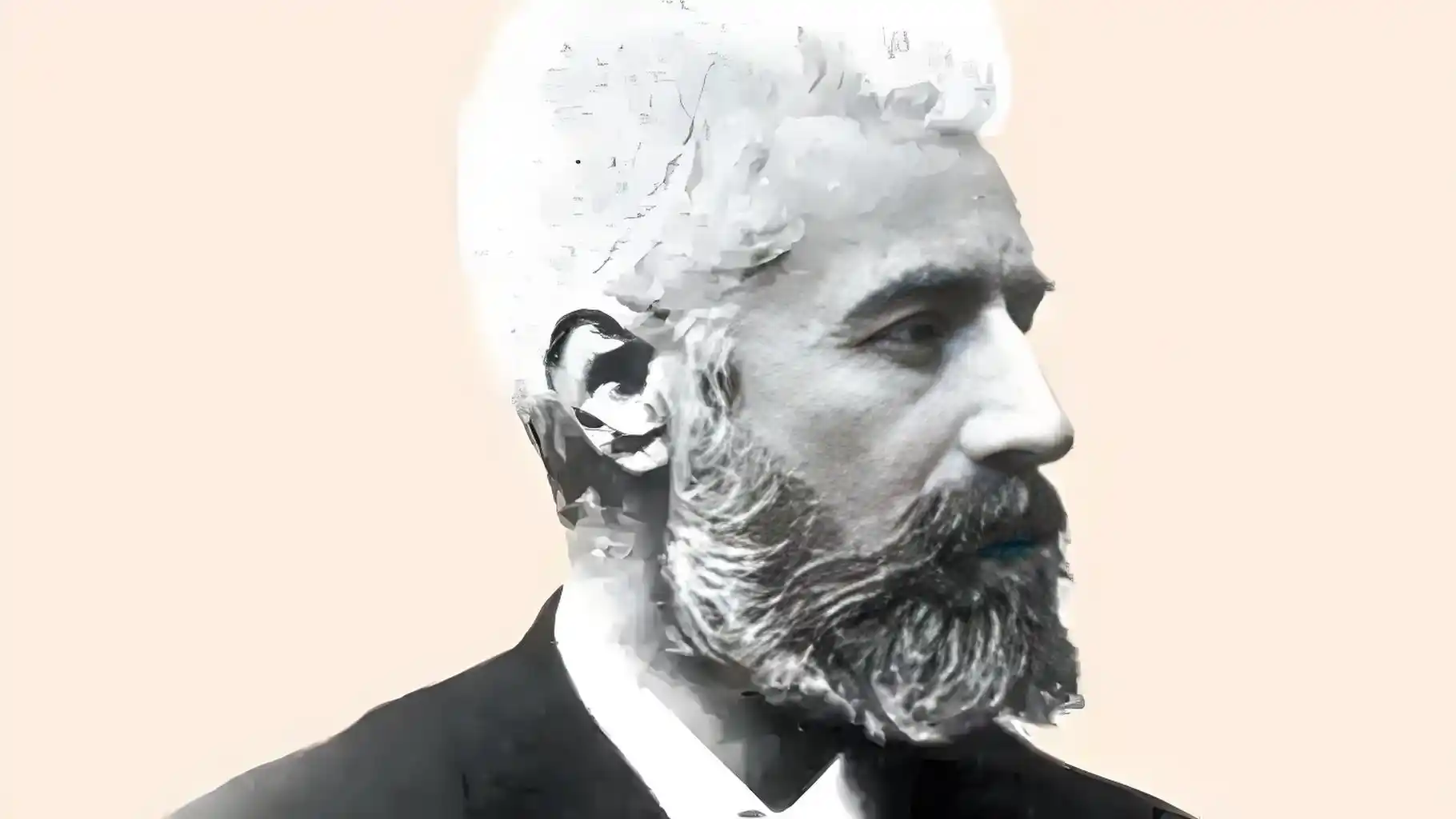

Who Was Aimé Guerlain?

Born in 1834, Aimé Guerlain was the second-generation heir to the French luxury house Guerlain, founded by his father Pierre-François Pascal in 1828. As the creative force behind the brand from 1864 until his death in 1910, he transformed perfumery from an elitist craft into an innovative art form accessible beyond aristocracy.His pioneering use of synthetic ingredients redefined scent creation forever.

The Birth of a Perfume Dynasty

Aimé grew up immersed in the world of raw materials and distillation. His father Pierre-François Pascal established Guerlain as the official perfumer to European royalty, creating bespoke scents for Napoleon III’s Empress Eugénie and Queen Victoria. When Pierre died in 1864, Aimé and his brother Gabriel inherited the business. While Gabriel managed operations, Aimé focused on artistry—studying botany, chemistry, and traditional techniques to elevate Guerlain’s creative legacy.

Early milestones under Aimé’s direction included:

- 1867: Bouquet de l’Exposition for the Paris World’s Fair.

- 1870: Modern lipstick prototypes and early sunscreen formulas 3. These innovations laid groundwork for his magnum opus—a fragrance that would shatter conventions.

Jicky: The Dawn of Modern Perfumery

In 1889, Aimé unveiled Jicky, a fragrance now celebrated as the first modern perfume in history. Why was it revolutionary?

The Science Behind the Scent

Jicky broke tradition by fusing natural essences with synthetic vanillin (vanilla aroma compound)—a technique unprecedented in 19th-century perfumery. This allowed layered “top, middle, base notes” to evolve on skin:

- Top Notes: Fresh bergamot, lemon, and rosemary.

- Heart: Lavender paired with jasmine and iris.

- Base: Vanilla-infused leather and woods 1 4.

Unlike single-note floral colognes of the era, Jicky’s complexity created an “abstract” emotional experience—a concept Aimé called “perfume as art”.

Democratizing Luxury

Synthetics made Jicky affordable. Previously, perfumes relied on rare naturals like jasmine absolute (requiring 8,000 flowers per 1ml). By supplementing with lab-crafted ingredients, Aimé slashed production costs. Jicky sold at one-third the price of royal exclusives like Eau de Cologne Impériale. Suddenly, Parisian bourgeoisie could access Guerlain’s genius—eroding the aristocracy’s olfactory monopoly.

Artistic Philosophy: Beyond the Formula

Aimé approached perfumery as “alchemy blended with poetry.” He believed scents should evoke memories and landscapes, not mimic nature. His studio walls displayed Japanese woodblock prints and Persian miniatures—visual inspirations for transportive accords like Eau de Cologne du Coq (1894), which captured “morning sunlight in a Mediterranean citrus grove”.

Critics initially scorned Jicky’s “unfeminine” lavender-leather fusion. Yet Aimé persisted:

“Perfume must speak to the soul, not conform to expectation.” By 1900, Jicky’s gender-fluid appeal made it a cult favorite among intellectuals and artists—proving his vision ahead of its time.

Landmark Creations

Beyond Jicky, Aimé’s portfolio included:

| Perfume | Year | Key Notes | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eau de Verveine | 1890 | Lemon verbena, citrus, pepper 1 | First “refreshing” summer cologne |

| Cuir de Russie | 1872 | Birch tar, lavender, musk 1 | Inspired Russian leather traditions |

| Eau de Cologne du Coq | 1894 | Neroli, oakmoss, lavender 1 | Homage to Mediterranean terroir |

Each expanded perfumery’s vocabulary—from spice routes (Russian Empire, 1879) to herb gardens (Menthol Pastilles, 1890).

The Guerlinade Signature

Aimé codified Guerlain’s signature DNA: Guerlinade. This proprietary accord blended vanilla, tonka bean, and iris into a “sensual, powdery trail.” Jacques Guerlain (Aimé’s nephew) later refined it in Shalimar (1925), but its core embodied Aimé’s belief that “a perfume should linger like a sonnet”.

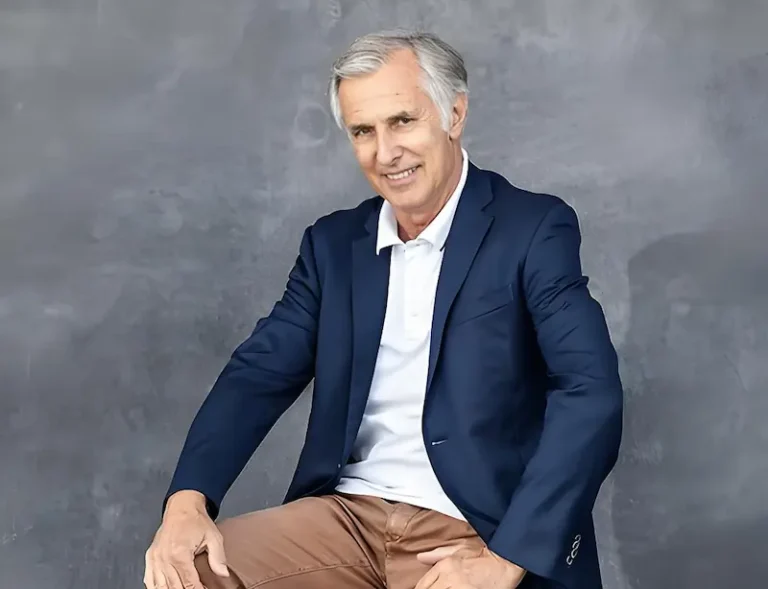

Passing the Baton

In 1904, Aimé mentored his nephew Jacques Guerlain as successor. Jacques credited Aimé’s notebooks—filled with molecular diagrams and poetry fragments—as the foundation for classics like L’Heure Bleue (1912). When Aimé died in 1910, obituaries hailed him as “the architect of perfumery’s future”.

Why Aimé Guerlain Still Matters

Industry-Wide Impact

- Synthetics Adoption: 95% of modern perfumes use synthetic ingredients—a direct legacy of Jicky’s innovation .

- Perfume Structure: His top-middle-base framework remains the global standard .

Cultural Legacy

Jicky is still produced today as Guerlain Jicky Extrait (9.5/10 on NoseTime). Exhibits at Paris’ Musée des Arts Décoratifs honor it as a “cultural monument”. In 2020, The New York Times included Jicky in “The 10 Scents That Changed History” for bridging tradition and modernity.

Final Thoughts

Aimé Guerlain’s genius lay in seeing perfume not as a luxury, but as a language. By marrying chemistry with artistry, he gave scent the power to narrate human emotion—forever altering how we wear memory and desire. As Guerlain’s current perfumer Thierry Wasser states:

“Every fragrance since 1889 is a conversation with Aimé.”

For enthusiasts exploring perfumery’s roots, Jicky remains the essential starting point—a bottled revolution that continues to whisper its creator’s name.